In a previous post, I discussed the nature of the conflict between neopositivistic and naturalistic epistemology regarding the normative status of epistemology for science. Here, I present a compelling criticism of Quine’s naturalized epistemology which suggests that shifting epistemology from philosophy to psychology does not accomplish everything Quine hoped it would.

Quine’s equivocation

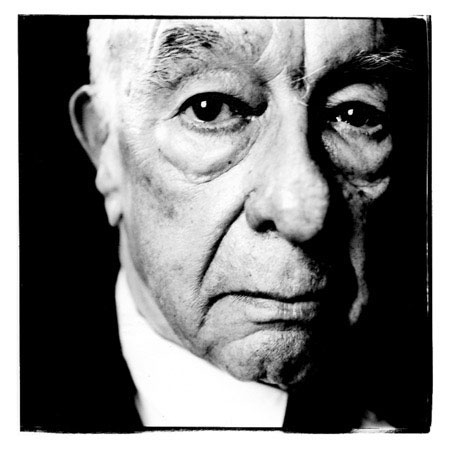

Harvey Siegel is a defender of Reichenbach’s separation of discovery and justification. He analyzed and criticized Quine’s position in his article from 1980 entitled “Justification, Discovery, and the Naturalizing of Epistemology.”

Quine’s criticism of neopositivism was largely aimed at Carnap’s failures at rational reconstruction, which was an attempt to redefine and reorder all knowledge based on the logical structure of scientific knowledge and method.

…why all this creative reconstruction, all this make-believe? The stimulation of his sensory receptors is all the evidence anybody has had to go on, ultimately, in arriving at his picture of the world. Why not just see how this construction really proceeds? Why not settle for psychology? …If we are out simply to understand the link between observation and science, we are well advised to use any available information, including that provided by the very science whose link with observation we are seeking to understand. (1)

Since rational reconstruction has failed, argued Quine, empirical psychology should become the means of understanding the link between observation and science.

However, Siegel asserts that Quine’s stated epistemological goal, namely to understand the link between observation and science, is equivocal.

It equivocates between distinct senses of “understanding the link”: (a) understanding the psychological mechanisms by which scientific theories are produced, and (b) understanding the criteria by which we select one link over and against other links, one theory over and against other theories. This latter sense, of course, demands the evaluation of competing theories; the former does not. It is the former sense, though, that is amenable to empirical psychological research; the latter is not. An account of the mechanisms of knowledge-acquisition, or the psychological processes involved in theory building, will account for the acquiring of theories we have rejected, as well as those we currently hold. Such an account, therefore, since it accounts for what we take to be “good” as well as what we take to be “bad” theories, cannot distinguish the good from the bad – which is to say, such an account cannot aid in justifying, or rationally preferring, one theory over another. (2)

This means that in some sense Quine has only naturalized half of epistemology. This plan to have cognitive psychology, or neuroscience, rather than philosophy, describe the mechanisms by which we arrive at scientific theories seems plausible. However, inasmuch as naturalized epistemology denies the need for an epistemological justification, it also fails to provide a means for the rational evaluation of theories.

Quine’s appeal to psychology can only help in accounting for the psychological mechanisms and processes of theory development – not in the rational evaluation of theory. Consequently, his appeal to psychology does not successfully challenge Reichenbach’s distinction between psychology and epistemology. (3)

According to Siegel, Quine succeeds in naturalizing the context of discovery and is happy for him to do so. Let the psychologists and scientists describe this link between observation and science. But even this approach to epistemology still requires a means or standard for choosing between theories.

I am not suggesting that philosophers, rather than scientists, make (or ought to make) scientific judgments which need to be justified. Scientists, not philosophers, assess the adequacy of [for example] competing accounts of the structure of space. To this extent I agree with Quine that there is no “first philosophy” stance from which philosophers govern, or pass judgment on, the work of scientists. However, when scientists assess the adequacy of competing accounts of some aspect of nature, they do so by offering arguments, by “making cases,” for one or another of the competing accounts. These arguments, or “cases,” have important general features, and these general features are themselves the object of study of epistemology.

An epistemologist qua epistemologist, does not pass judgment on competing accounts of the structure of space; he/she does, however, study the general features of such scientific judgments, and tries to develop an account of the justificatory force of such (scientific) judgments – that is, an account of why the judgments made in the special sciences are (or are not) properly considered justificatory. And it is to this sort of account, I have been arguing, that psychology cannot contribute. (4)

There is no branch of the natural sciences that performs analysis of epistemological justification, yet it is still needed, even if we grant Quine his argument. For Siegel, establishing a psychological, or neuroscientific, description of the link between observation and science does not abrogate the need for standards of judgment between competing claims. Even naturalistic epistemology must choose between competing scientific theories, a function which empirical psychology alone cannot perform. In some sense, then, Quine was only half right, or was only right about the nature of half of epistemology.

***

Siegel’s criticism of naturalized epistemology further highlights the tension between neopositivistic and naturalistic epistemology, which I introduced in the last post. In the the next post, I’ll discuss the implications of this tension for Ladyman and Ross’s epistemological commitments, as well as for their project as whole.

Notes

- W.V.O. Quine, “Epistemology Naturalized,” p. 75-6 in Harvey Siegel, “Justification, Discovery, and the Naturalizing of Epistemology,” p. 318.

- Siegel, “Justification, Discovery, and the Naturalizing of Epistemology,” p. 319.

- ibid., p. 319.

- ibid., p. 320.

2 thoughts on “Quine was half right”