There are several questions that motivated all the thinkers involved in the development of 20th century empiricism and philosophy of science that need to be stated explicitly. Often, these are the sorts of questions which, for everyone involved in the conversation, are presupposed and therefore, are never (or rarely) stated outright. And even if they are stated, at times the arguments can become so complex that we amateurs lose the forest for the trees.

How empiricists could provide an account of mathematics is one such question.

An all-too-simplistic historical background

Many of the historical debates over divergent theories of knowledge orient around claims about sources of knowledge. Where does human knowledge come from? Divine revelation? Our five senses? Intuition? Careful, discursive reasoning? All of these sources, and others, have been suggested throughout human history as reliable sources of information about reality.

For Plato, the concept of innate ideas was a viable possibility for explaining human knowledge. Accordingly, the soul contains deeply forgotten truths about reality, God, and itself which, under the right conditions, it can recollect. Recollection is not dependent upon sensory experience of the world. Rather, these truths can be learned, or discovered, though the use of pure reason alone.

While recollection fell out of favor with the passage of time, the existence of disciplines such as logic and mathematics, which were also sensory-independent, were looked to by the Enlightenment Rationalists (i.e. Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz) and German Idealists (i.e. Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel) as obvious cases in which pure reason functioned as a source of knowledge about reality.

Empiricists, however, following a more Aristotelian model, claimed that all our knowledge was gained through our five senses. Broadly speaking, the British Empiricists Locke, Berkeley, and Hume all claimed that our experiences, the associations we recognize among them, as well as the logical inferences we draw from them are all we possess on our epistemic endeavors. Still, mathematics posed a challenge to empiricists.

How is pure mathematics possible?

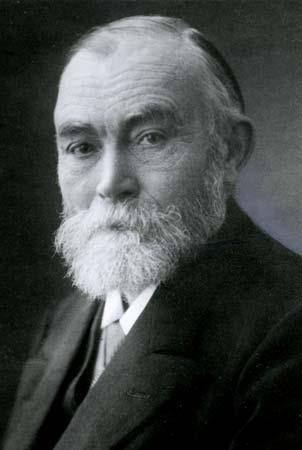

Mathematics was a discipline with true propositions that provided certitude, but were not dependent on observation of any kind. But thanks to the new symbolic logic invented by Gottlob Frege (pictured above) and developed by Russell and Whitehead, empiricists were in a position to answer the question. Because Frege had deduced arithmetic from logic, it was hoped that the whole of mathematics could be similarly deduced. So doing would demonstrate that mathematics was analytic and therefore, not a threat to empiricist theories of knowledge.

If the propositions of logic were analytic, and mathematics could be deduced from logic, then the propositions of mathematics were also analytic. Empiricists could accept the truth of mathematical propositions as analytic with ease because analytic knowledge is not, in fact, knowledge about reality as the Rationalists and Idealists had always claimed.

What does it mean to call mathematics “analytic”? Consider the classic example “All bachelors are unmarried.” What it means to be “unmarried” is contained within the concept of “bachelor”. As such, no new information about reality is gained from the proposition. If you understand the concept of bachelor, then you already understand the concept of unmarried.

Put slightly more formally: an analytic statement is one in which the content of the predicate does not add information about the concept of the subject. If mathematics is fundamentally logical, then mathematical propositions are analytic and thus, they are not an argument against empiricist theories of knowledge. Frege, Russell, and Wittgenstein went on to argue precisely this.

***

However, in order to avail themselves of this understanding of mathematical propositions, empiricists had to robustly accept Kant’s analytic/synthetic distinction. Which they did. The role this distinction played for the logical positivists, logical empiricists, and Quine will be the subject of forthcoming posts.

2 thoughts on “The value of an empiricist account of mathematics”