Another motivating question for 20th century empiricism was the nature and status of Kant’s analytic/synthetic distinction. Frege, Russell, Whitehead, Wittgenstein, Carnap and others all accepted this distinction, though the significance of distinction changed over time. Famously, Quine rejected it and viewed analytic and synthetic statements as different in degree, but not in kind.

In this post, I briefly sketch Kant’s distinction and briefly introduce Wittgenstein’s transformation of the analytic into the tautological. This developments are crucial to understanding the later Carnap/Quine debate.

An all-too-simplistic account of Kant’s analytic and synthetic

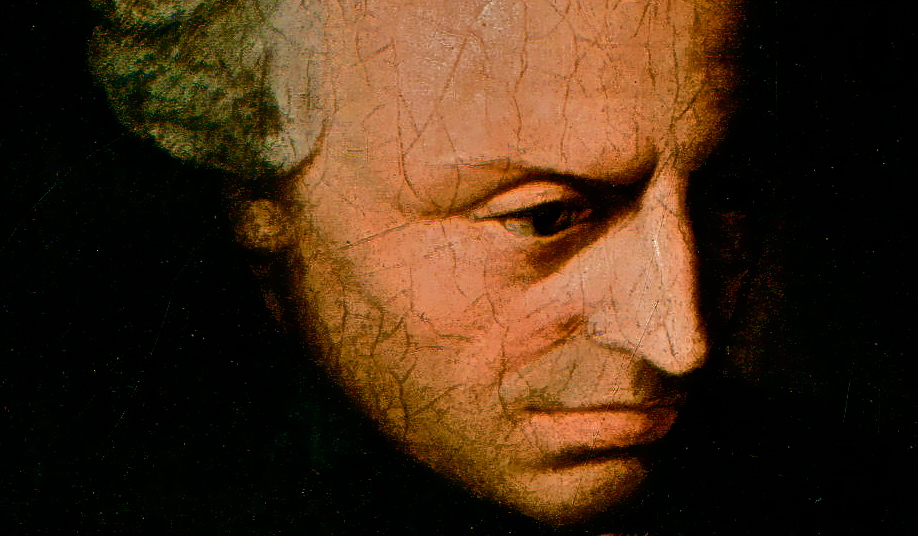

In his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant was inspired by Hume’s criticism of causation to both provide an account of the conditions of empirical knowledge and limit the scope of metaphysical speculation. Unlike Descartes, whose method of universal doubt left our knowledge of the external world in question, Kant accepted that scientific investigation provided knowledge about the world. But such confidence in science alone did not provide an empiricist account of mathematics.

Kant distinguished between analytic and synthetic propositions. Analytic propositions are those in which the content of the predicate is already contained within the concept of the subject. For example, “all bachelors are unmarried,” or “a triangle has three sides.” Synthetic propositions are those in which the content of the predicate is not already contained within the concept of the subject. “All bachelors are alone” is an example used by Kant.

In other words, analytic propositions do not add new information to the subject of the sentence, while synthetic propositions do add new information to the subject of the sentence. As such, Kant argued that analytic propositions are not cases of knowledge about reality, but are merely true in virtue of their meaning, or the logic of their construction.

Additionally, Kant distinguished between a priori and a posteriori propositions. A priori propositions do not rely on experience or observation to be true, while a posteriori propositions do rely on experience or observation in order to be true. The examples from above can be used here as well: “all bachelors are unmarried” is an a priori proposition and “all bachelors are alone” is an a posteriori proposition.

These four kinds of propositions can be combined into the following types:

- Analytic a priori

- Synthetic a priori

- Analytic a posteriori

- Synthetic a posteriori

Analytic a priori propositions clearly occur. An example is, again, “all bachelors are unmarried.” Synthetic a posteriori propositions clearly occur as well, an example being that “all bachelors are alone.”

What about analytic a posteriori propositions? Kant concluded these propositions were contradictions, as it could not be the case that the content of the predicate is already contained within the concept of the subject and that the proposition relied on observation to be true.

This leaves the synthetic a priori. Kant concluded that mathematical propositions were synthetic a priori statements. The proposition “7 + 5 = 12” is a case where observation is not required in order to make the proposition true (i.e. a priori), but also a case in which the content of the predicate “is equal to 12” is not contained within the subject “7 + 5” (i.e. synthetic). By demonstrating that synthetic a priori knowledge existed, he produced an empirical (i.e. synthetic) account of how mathematics was possible.

From analytic to tautological

Russell, Wittgenstein, and the logical positivists, however, we not persuaded by Kant’s argument that mathematics was synthetic. For them, mathematical (and logical) statements were purely analytic. Wittgenstein declared that the truths of mathematics and logic were not merely analytic, but were in fact tautologies. By this he meant that they had no relation to facts is in the world nor did they represent anything about the world, but were empty, formal structures. Stephen Schwartz glosses the significance of Wittgenstein’s advancement in the Tractatus:

Wittgenstein’s use of truth tables to demystify logic and mathematics provided the fuel for the logical postivist locomotive. Frege, Russell, and Whitehead, according to Wittgenstein, had accomplished a brilliant feat in showing that mathematics could be derived from logic, but they did not fully grasp what they had done. Frege and Russell still had ideas about self-evidence and pure reason floating around. Although Russell held that mathematics was analytic, he did not at first realize the implications of this. Russell was still yearning for some sort of intellectually satisfying certainty, whereas according to Wittgenstein the only certainty available is empty and formal. (1)

Wittgenstein’s development of the analytic into the tautological deepened the sense in which mathematics and logic could not be considered knowledge of the world via pure reason as the Rationalists and Idealists had claimed.

The current relevance

Keeping these large, motivating questions in mind while reading the detailed and complex discussions of a Carnap, or Quine, or a Siegel is helpful.

Previously, I have discussed how the status of mathematics was an historical obstacle for empiricism. In this post I have discussed more fully the role that the analytic/synthetic distinction played in the question concerning mathematics.

In a forthcoming post, I will discuss Quine’s rejection of the analytic/synthetic distinction, as well as the role this rejection plays in his naturalism and the web of belief. I also plan to discuss some of the debate between Carnap and Quine on this and other issues.

However, before doing so, I want to flesh out some of philosophical commitments of the logical positivists. Quine’s naturalism is a direct reaction to logical positivism and must be understood in that light.

Notes:

- Stephen P. Schwartz, A Brief History of Analytic Philosophy: From Russell to Rawls, p. 53.

One thought on “The analytic/synthetic distinction”