I’m at something of a standstill at the present moment.

Writing a dissertation is a constant pivot between extremely detailed analysis and high-level organization. If I focus for too long on either aspect, I tend to lose sight of the other. Get too deep in the weeds, lose track of the larger narrative.

These research outlines represent an attempt to recapture the narrative. I’m trying to step back, view some major pieces of the argument, see how they relate to one another, and make sure I have the literature to support each stage of my argument. Each outline provides the framework for part of that larger argument.

Psychologism

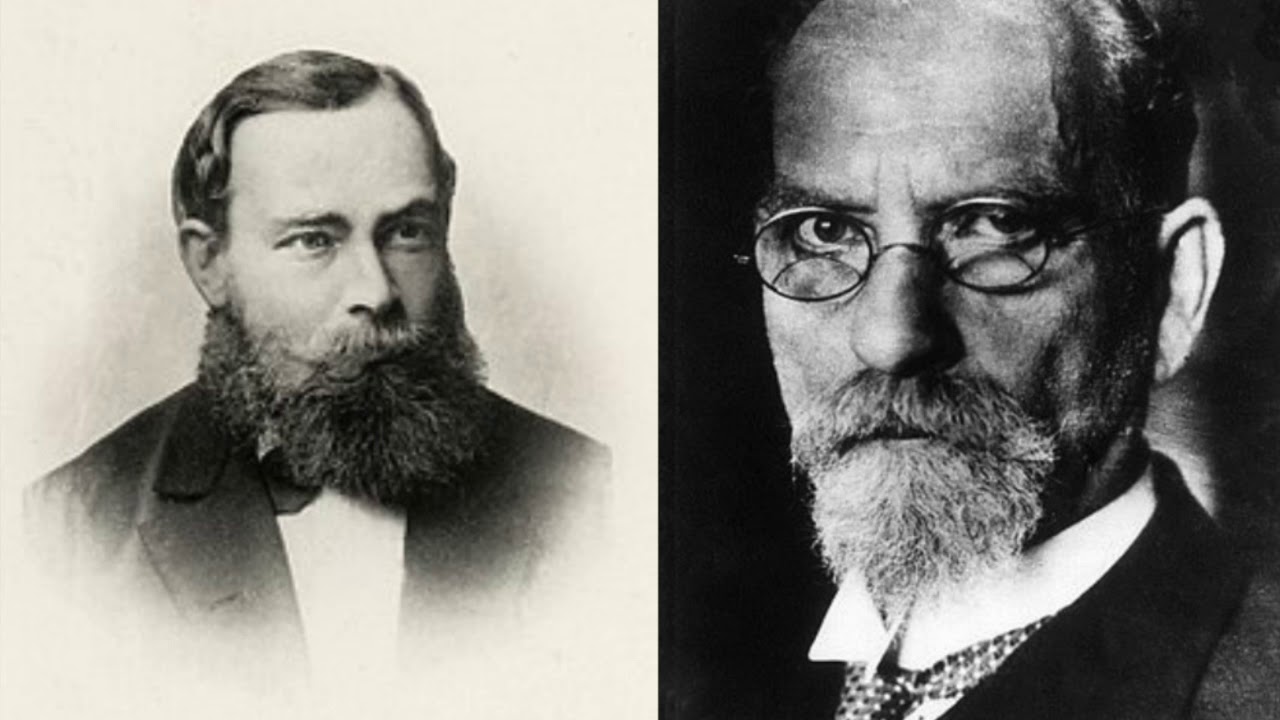

Antipsychologism originates from Frege and Husserl, is presupposed by the logical positivists, is operative in Quine’s naturalized epistemology, and continues in Ladyman and Ross’s project to naturalize metaphysics.

Sober’s article discusses and critcizes Frege’s original, antipsychologistic arguments, specifically his variability argument, which was adopted by Reichenbach and the logical positivists as the separation between the context of discovery and the context of justification. Siegel defends the postivistic separation of contexts, weighing recent objections to it and finding them wanting. Kusch’s book details the relevant historical factors to the first 40 years of the debate. McCarthy’s book, like Kusch’s, makes the argument that the antipsychologistic turn originating with Frege was both unnecessary and a significant mistake.

Elliott Sober, “Psychologism,” Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, Vol. 8 (July 1978), pp. 165-191.

(Abstract)

This paper tentatively defends the psychologistic thesis that logic describes “the laws of thought” – that rules of rational inference have “psychological reality.” The strategy of argument is to show that psychologism is immune from some familiar philosophical objections and is moreover a fruitful working hypothesis in cognitive psychology. The first part critically examines Frege’s “variability argument” against psychologism, which the positivists used to support their view that there is no logic of discovery. I then discuss how psychologism might account for cases of error and irrational inference, and how numerous explanations in cognitive psychology conform to the psychologistic pattern of analysis. The claim that psychologism is a priori true is then criticized, and some observations are made about the psychological considerations that are present in antipsychologistic epistemology.

Harvey Siegel, “Justification, Discovery, and the Naturalizing of Epistemology,” Philosophy of Science, Vol. 47, No. 2 (June 1980), pp. 297 – 321.

(Abstract)

Reichenbach’s well-known distinction between the context of discovery and the context of justification has recently come under attack form several quarters. In this paper I attempt to reconsider the distinction and evaluate various recent criticisms of it. These criticisms fall into two main groups: those which directly challenge Reichenbach’s distinction; and those which (I argue) indirectly but no loess seriously challenge that distinction by rejecting the related distinction between psychology and epistemology, and defending the “naturalizing” of epistemology. I argue that there recent criticisms fail, and that the distinction remains an important conceptual tool necessary for an adequate understanding of the way in which scientific claims purport to appropriately portray our natural environment.

Martin Kusch, Psychologism (London: Routledge, 1995).

(Book summary)

For most of this century, Western philosophy has been resolutely antinaturalist, and until recently the sharp distinction between the empirical sciences and philosophy seemed almost self-evident: the questions of why they should be separate, and of how they came to be separate, were never asked. These questions are at the heart of Martin Kusch’s groundbreaking study.

Antinaturalism rose to dominance in the debate on psychologism among German academic philosophers at the turn of the century. Psychologism, according to received opinion, was decisively refuted by Frege and Husserl. Kusch therefore examines their arguments and, crucially, relates them to the context that shaped that debate and gave those arguments their persuasive force. Drawing on perspectives pioneered by the sociology of scientific knowledge, he reconstructs the dynamics of the psychologism debate; he uncovers its causes and weighs the factors that determined its outcome. What emerges is the fascinating picture of a struggle, between ‘pure’ philosophy and the newly emerging experimental psychology, for academic status, social influence and institutional power. The triumph of antinaturalism, far from being the only logical conclusion, was dependent on historical contingency.

Michael H. McCarthy, The Crisis of Philosophy (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990).

(Back Cover)

This book presents a sympathetic yet critical treatment of the major philosophical attempts to define a viable project for philosophy in the face of historical changes. McCarthy, then, proposes a comprehensive, critical, and methodological strategy of epistemic integration that fully respects the progressive and pluralistic character of contemporary science and common sense.

The programs of Frege, Husserl, Wittgenstein, Carnap, Sellars, Dewey, Quine, and Rorty are carefully presented and an assessment is made of their merits and limitations. This assessment results in a defense of Lonergan’s integrative strategy – a nuanced philosophical strategy around which a gathering central could be built. McCarthy presents Lonergan’s work as containing the firm outline and partial execution of a philosophical project continuous with philosophy’s historic purposes and equal to the exigences of the present.

The book examines a broad range of seminal topics and, after extended dialectical treatment of them, develops a coherent account of their interdependence. These topics include psychologism, intentionality, the limits of naturalism, semantical and epistemic realism, historical belonging, epistemic invariance, foundational analysis, the limitation of logic and of the linguistic turn, generalized empirical method, the interdependence of mind and language, the interplay of nature and history, and the critical appropriation of tradition.