Let’s continue with McCarthy’s (and Lonergan’s) distinction between classical and historical consciousness. In my last post, I quoted McCarthy at length on Aristotle’s conception of science and how elements of that conception linger in the background of contemporary philosophy of science debates. Here, I’ll quote McCarthy at length on the modern shift from Aristotle’s classical consciousness to historical consciousness.

Historical consciousness

This quote picks up where McCarthy’s quote in my previous post leaves off:

“This confidence was shaken by the Copernican revolution in physics, which led in time to the repudiation of Aristotle’s cosmology. Through the discoveries of Kepler, Galileo, and Newton, the axiomatic principles of Aristotle’s physics were shown to be neither evident, certain, nor true. But the logical ideal of science first articulated by Aristotle retained its power even as his specific scientific theories were openly denied. The Cartesian quest for certainty, with its insistence on intuitively evident axioms, its conception of science as a permanent individual achievement, and its aspiration to true certain knowledge of causal necessity, retains the Aristotelian or classical legacy nearly unimpaired. It is true that Aristotle’s concept of causality was abandoned by modern physics and replaced with a heuristic ideal based on invariant mathematical laws; and it is also true that the moderns subordinated theoretical understanding to practical power as the primary motive of science. But, with these important exceptions, the classical theory of science was faithfully preserved. The relentless search in modern rationalism and empiricism for indubitable foundations on which to erect the structure of science is unintelligible without the tacit acceptance of the classical ideal. The problem of knowledge dominates modern philosophy insofar as it tried to fit modern scientific theories to the classical theory of science. Kant’s Copernican revolution in epistemology, despite its radical reconception of the metaphysical standing of the object of science, is still conservative in its endorsement of the classical position. For Kant, Euclidean geometry, Newtonian mechanics, and Aristotelian formal logic are all permanent theoretical achievements. Pre-critical philosophers had failed to uncover the full conditions of their possibility and thus had erred in their metaphysical interpretation, but they had not erred in upholding universality, strict necessity, and apodicticity as essential criteria of scientific knowledge.

“As E.W. Beth has argued, there were dissenters from the Aristotelian canons of science in pre-Kantian thought but they were a distinct minority. The classical conception of science survived the skeptical spirit of modernity. By its survival, it imposed on philosophy a distinctive conception of epistemology. Given that science must be a logically organized structure of truths founded on self-evident axiomatic principles, philosophy’s task was to uncover those underlying principles, to establish their certainty, and to show at least in principle, how the legitimate scientific disciplines could be reconstructed on this foundational base. Epistemic skeptics, like Hume, swim against the tide with their denial that this program can be executed. Hume’s quarrel, however, is not with the definition of the project but with the power of human reason to complete it.

“Despite significant changes in belief, intension, categorical framework, heuristic structure, and metaphysical conviction, the theoretical realm of meaning preserved its identity for two thousand years through constant adherence to the classical theory of science first outlined in Aristotle’s logic. That theory imposed on scientific inquiry a rigorous normative ideal, and it imposed on philosophy the task of monitoring scientific compliance with it. But in the nineteenth century, as the result of diverse cognitive pressures, the classical conception of science was subverted. By this I do not mean that philosophers universally abandoned it or that scientists explicitly repudiated it. Rather, it lost touch with the heuristic anticipations of actual scientific practice and eventually with the implicit meaning of the term science as used by those within and without the scientific community. One way to describe the shift from classical to historical consciousness is to note that scientists surrendered the quest for epistemic certainty and adopted the ideal of complete explanatory understanding. Rather than perceiving the revision and replacement of scientific theories as a sign of defeat or failure, scientists came to view fundamental theoretical revisions as occasions of triumph. These revision, in turn, were not expected to be permanent achievements but relatively stable systematizations of understanding subject to to further development and refinement. Classical consciousness defined science in terms of an allegedly finished propositional achievement; its successor, historical consciousness, defined it as an ongoing normative process of inquiry, unified by canons of method, resulting in a continuing succession of theoretical systems. No longer an affair of solitary individuals, science has become an essentially communal enterprise, marked by the specialization and division of labor, open to the collaborative sharing of controlled belief, and unified by the constant of empirical method. It no longer seeks theoretical invariance in permanent essences, unchanging natural laws, self-evident principles, or perfected categories of explanation but in the operative method by which laws are discovered and verified and categories and principles revised and refined. Bernard Lonergan’s compact formulation effectively summaries this most profound cognitive change:

“‘The Greek formulation as envisaged by Aristotle demands of science true certain knowledge of causal necessity. But: 1) Modern science is not true by only on the way to truth. 2) It is not certain; for its positive affirmations it claims no more than probability. 3) It is not knowledge, but hypothesis, system and theory, i.e. the best scientific opinion of the day. 4) It’s object is not necessity but verified possibility. Natural laws aim at stating not what cannot possibly be otherwise but what in fact is so. 5) Finally, while modern science speaks of causes, still it is not concerned with Aristotle’s four causes of end, agent, matter and form, but with verifiable patterns of explanatory intelligibility. For each of the five elements constitutive of the Greek ideal of science, the modern ideal substitutes something less arduous, more accessible, dynamic and effective.’

“The transition from classical to historical consciousness had decisive implications for philosophy. At approximately the same time that philosophy lost its metaphysical authority over science, it lost its epistemic function of testing the compliance of actual scientific theories with the classical ideal of knowledge. Scientific practice proceeded without concern for philosophical direction and approval, while philosophy, deprived of its traditional theoretical functions, became divided and uncertain about its cognitive purpose.” (1)

Logical positivism – classical or historical?

The five elements of modern science mentioned by Lonergan above are constitutive of, say, the conception of science about which the logical positivist philosophized. That seems uncontroversial. But the more I read about some of their central concerns, and especially about Quine’s criticisms of those central concerns, the more I question whether epistemological debates in 20th century philosophy of science are still struggling to understand what to do with particular elements of Aristotle’s legacy.

To be more specific, I have mind the contemporary question about the relationship of psychology, epistemology, and logic. A basic distinction between the order of inquiry and the order of demonstrated knowledge seems, to me, entirely legitimate. However, Frege’s logicism, an attempt to banish psychology from logical analysis, made the distinction so forcefully that I wonder whether any philosophy of science influenced by logicism (i.e. logical positivism, logical empiricism, and strains of naturalism) possess the tools necessary to achieve its own goals.

Again: can one fully account for the nature and success of the modern conception of science through logic alone? Further, by excluding the context of discovery from what is considered “proper logic and epistemology of science,” how is this not the same as Aristotle’s conception of science as a logic of “demonstrated knowledge”?

In other words, is the debate over the relationship between psychology, epistemology, and logic an extension of Aristotle’s division between the order of inquiry and the order of demonstrated knowledge, and his conception of science as the latter? If so, is this debate ultimately a mistaken attempt to reconcile an element of classical consciousness with modern science?

I don’t know the answer to this question. I also don’t know if I’m even asking the question properly. As Lonergan would say, perhaps the moment of clarity I take this question to capture is actually an inverse insight, or an expectation of intelligibility somewhere where there is, in fact, none. We’ll see.

Notes:

- Michael H. McCarthy, The Crisis of Philosophy (Albany: SUNY Press, 1990), 8 – 10.

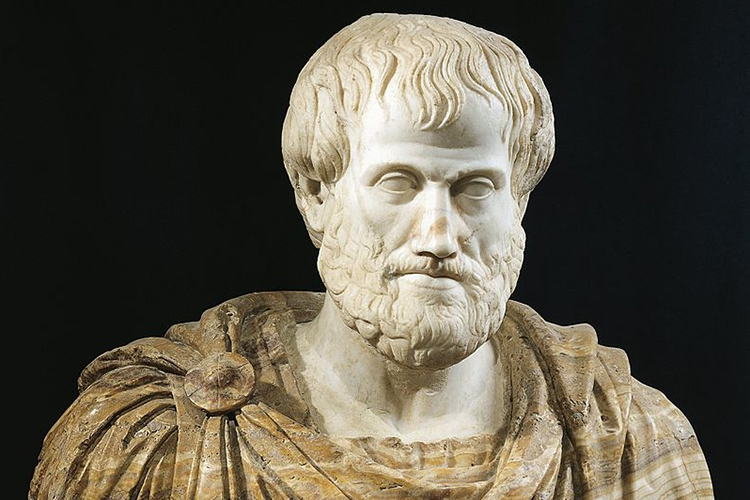

One thought on “Aristotle subverted”