Previously I outlined what Stephen P. Schwartz takes to be the central tenets of logical positivism. Here I’ll focus on the textual sources of logical analysis as a philosophical method.

While not first chronologically, Hans Reichenbach’s 1938 Experience and Prediction summarizes the intent of the logical positivist project concisely:

It is the intention of uniting both the empiricist conception of modern science and the formalistic conception of logic…which makes the working program of this philosophic movement. (1)

I’ve already mentioned the empiricist motivations of the logical positivists, as well as the excitement generated by the developments in mathematics, which were applied to logic too.

Here I highlight some of the sources of logical positivism as a “philosophic movement”.

Logical analysis as philosophical method

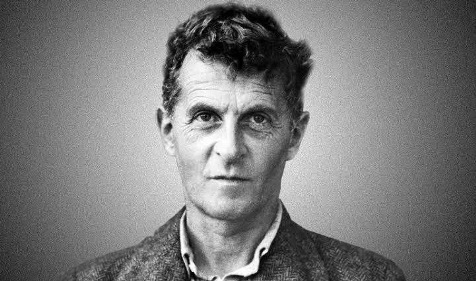

Wittgenstein’s work in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was the culmination of the work of Frege, Russell, and Whitehead. Frege reduced arithmetic to the principles of logic. Subsequently, Russell and Whitehead attempted to reduce the whole of mathematics to the principles of logic. Wittgenstein’s work attempted to articulate the logical structure required to mediate between thinking/speaking about the world and the states of affairs in the world.

However, the Tractatus is short on argumentation. In most cases, Wittgenstein seems to stipulate rather than justify his claims, which is as true his conception of philosophical method as it is for anything else:

4.11 The totality of true propositions is the whole of the natural science (or the whole corpus of the natural sciences).

4.111 Philosophy is not one of the natural sciences.

4.112 Philosophy aims at the logical clarification of thoughts. Philosophy is not a body of doctrine but an activity. A philosophical work consists entirely of elucidations. Philosophy does not result in ‘philosophical propositions’, but rather in the clarification of propositions. (2)

And again:

6.53 The correct method in philosophy would really be the following: to say nothing except what can be said, i.e. propositions of natural science – i.e. something that has nothing to do with philosophy – and then, whenever someone else wanted to say something metaphysical, to demonstrate to him that he has failed to give a meaning to certain signs in his propositions. Although it would not be satisfying to the other person – he would not have the feeling that we were teaching him philosophy – this method would be the only strictly correct one. (3)

Given his conception of philosophy, Wittgenstein’s style makes sense. If something just is the case, then just say so. No further argumentation is required.

Positively stated, the task of philosophy is to elucidate what is known to be the case (i.e. the propositions of science) through precise and careful formulation of those propositions. Negatively stated, the task of philosophy is to disabuse people of their erroneous questions and concepts by means of the logical elucidations of language.

Carnap rigorously develops Wittgenstein’s concept of philosophical method in his 1932 “The Elimination of Metaphysics through the Logical Analysis of Language”:

But what, then is leftover for philosophy, if all statements whatever that assert something are of an empirical nature and belong to factual science? What remains is not statements, nor a theory, not a system, but only a method: the method of logical analysis. The foregoing discussion has illustrated the negative application of this method: in that context it serves to eliminate meaningless words, meaningless pseudo-statements. In its positive use it serves to clarify meaningful concepts and propositions, to lay logical foundations for factual science and for mathematics. The negative application of the method is necessary and important in the present historical situation. But even in its present practice, the positive application is more fertile. We cannot here discuss it in greater detail. It is the indicated task of logical analysis, inquiry into logical foundations, that is meant by “scientific philosophy” in contrast to metaphysics. (4)

In his 1939 “What is Logical Analysis,” Friedrich Waismann, another member of the Vienna circle, echoes Carnap and takes Hume’s analysis of the concept of causality as logical analysis par excellence:

Now what can be gained through philosophy is an increase in inner clarity. The results of philosophical reflection are not propositions but the clarification of propositions. Wherever real progress has been made in the history of philosophy, it resided not so much in the results as in the attitude to the questions: in what was regarded as a problem, or alternatively, in what was recognized as a falsely formulated question and excluded as such. Thus when Hume showed in his famous critique of the concept of causality that we only perceive the succession of events and never an inner bond that ties them together, the permanent gain from his reflection did not reside in a philosophical proposition – an axiom around which other propositions cluster as around a crystal of truth – but in the clarification of the sense of causal propositions; and hence not in an increase in the number of propositions but rather in its diminution: in the disposal of all that baggage of seeming truths and imagined knowledge that trailed behind that false idea. Hume analysed the concept of causality; and in this sense, philosophy can be called the logical analysis of our thoughts. (5)

Philosophy, then, as logical analysis becomes the handmaiden of science. Its task is to clarify the structure and meaning of the terms employed in scientific descriptions of the world. It should not itself make claims about the world, but engage in the activity or method of clarifying the only legitimate claims that can be made about the world, namely those of empirical science.

Notes:

- Hans Reichenbach, Experience and Prediction, v.

- Carl Hempel, Philosophy of Natural Sciences, p. 16.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, pp. 29 – 30.

- ibid., p. 89.

- Rudolf Carnap, “The elimination of metaphysics through logical analysis of language,” p. 77.

One thought on “Logical analysis as philosophical method”