In a previous post, I referred to the distinction between regarding human knowers as subject or as object, along with the implications of this distinction for how we understand the relationship between commonsense and science. Here, I’d like to elaborate on what is meant by regarding the human knower as subject.

Below is a sketch of an argument. Much of what follows is, at this stage, merely asserted rather than demonstrated. Please bear that in mind.

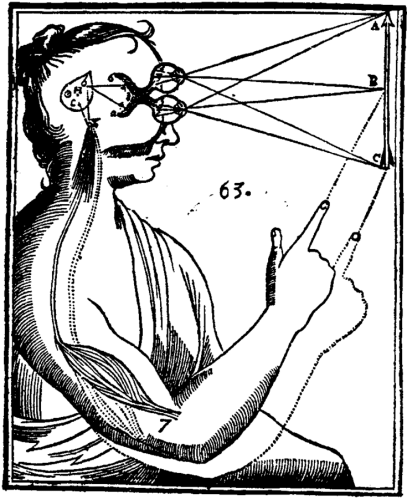

It means that we regard the knower as an intelligence who is consciously aware of various cognitive processes through which he proceeds in the act of knowing. At a high level, a knower experiences, understands, and judges various data, patterns, formulations, propositions, and evidence through any full circuit of knowing. These cognitive processes, as well as the shifts between them, are all consciously transparent occurrences within the knowers’ awareness.

Neurological correlates

There are, of course, neurological correlates for each of these consciously transparent processes. However, direct reference to them is unnecessary when giving an as subject analysis of human knowing for the simple reason that these neurological correlates are not consciously transparent to us.

By this I mean that the neurological correlates are not the appropriate objects of conscious, as-subject activity. We are neither consciously aware of them nor can we consciously control them, not directly.

As subjects, we intentionally shift between questioning, wondering, observing, understanding, considering, judging, etc. These conscious shifts result in corresponding shifts in neurological activity. They are, so to speak, the consciously transparent commands that result in the underlying neurological shift. They are the intermediary through which we shift the underlying neurology.

The necessity and sufficiency of consciously transparent analysis

The consciously transparent processes, therefore, are necessary and sufficient for both engaging in and analyzing human knowing.

There are two reasons for this.

First, the consciously transparent processes are necessary to teach individuals about reliable methods of knowing, as well as correcting them when they err. One could not teach or correct someone’s epistemic procedure through encouraging heightened activity of one neural pathway while simultaneously demanding suppression of activity from another except through calling attention to the consciously transparent commands.

Second, the consciously transparent processes alone have produced the methods of inquiry that have reliably resulted in our current descriptions of the underlying neurological correlates. In other words, neuroscience is discovered and produced by scientists, philosophers, and naturalists who attend to their experiencing, understanding, and judging as consciously transparent processes.

Necessary disclaimers

To repeat, the claim that attending to consciously transparent processes alone is necessary and sufficient to account for the as subject activity of human knowing is not a denial of the fact that these processes are produced by our underlying neurological structures and activities. Nor does this claim deny that our understanding of these as-subject, conscious processes can be deepened and enriched by a better understanding of the underlying neurology operative within them.

Additionally though, we can deny neither the necessity nor sufficiency of consciously transparent, as-subject analysis of our cognitive processes, nor can we deny that these same processes are produced by our underlying neurological activity which we can describe without reference to consciousness. Basically, we can regard our cognitive processes as subject or as object.

One of my guiding concerns is to reconcile these two perspectives regarding human knowers without explaining away either.

Descartes’ solution asserted that the mental and the material were distinct ontologies, or orders of being. Much subsequent philosophy which rejected his dualism tended to reject either the mind (i.e. materialism) or the body (i.e. idealism).

Lonergan’s solution claims that we are simultaneously intelligent and intelligible, that we can shift between regarding ourselves as either intelligent subject or intelligible object, and that it is when we aren’t mindful of the shift that we create confusion.

One thought on “The human knower as subject”