Elsewhere, I have argued that it is both necessary and sufficient to articulate a theory of knowing by analyzing the consciously transparent processes and operations of the knower. I want to deepen that argument by referring to Robert Henman’s work, in which he makes the argument that a more robustly articulated theory of cognition (i.e. of consciously transparent, mental acts or operations) can improve the work of neuroscientists engaged in mapping the neurological correlates of conscious mental activity.

The role of conscious mental acts in neuroscientific experiments

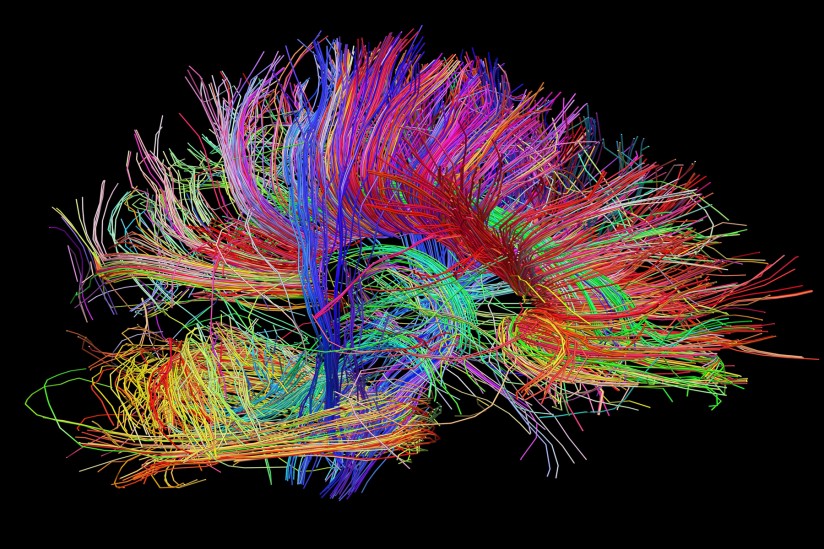

First, consider a common way of structuring an experiment designed to gather images of neurological activity through various scanning techniques.

There are different techniques presently used in neuroscientific research. The following are six conventional ways of gathering data in the neurosciences: 1) electroencephalography technique (EEG), 2) MRI scans, 3) fMRI scans, 4) near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), 5) positron emission tomography (PET), and 6) magnetoencephalography (MEG).

Neuroscientists are attempting to “map” the brain and to determine the functions of different areas of the brain and the interactions among them. By doing so neurocognitive scientists are attempting to develop of theory of thinking. In turn, neuropsychologists are studying relationships between the functioning of the brain and human behavior, as well as searching for the breakdowns responsible for diseases such as schizophrenia, autism and Down’s syndrome. The six techniques listed above gather data that reveal activity between brain locales that correspond to conscious operations and cognitive experiences. Correspondence is established empirically by measuring the simultaneous or sequential occurrences of mental acts and the brain activities. Verification of these correlated events is achieved by the repetition of experiments. There are differing types of data generated by the different techniques of “mind mapping”, but the data are similar because they are technically produced images or scans of cerebral activity…

Test are developed to evoke specific mental operations (paying attention, puzzling, memory, reasoning, decision-making, planning, speaking) and conscious states such as emotions and moods. One purpose in pursuing more specific and detailed descriptions of cerebral activity is to determine the causes of certain brain disorders linked to genetic mutations. It is hoped that such studies may lead to the prevention of some disorders as well as a better understanding of the genetic development of the human brain. (1)

Interestingly, accurate interpretation of the graphs and images that result from the techniques described above are heavily dependent upon the conscious mental operations which the test subjects are asked to perform. Those running the experiment no doubt take care to give specific and uniform instructions to the test subjects, but the results are, in fact, dependent upon accurate and clear communication, interpretation, and performance of the commands issued.

It cannot be overlooked, then, that our ability to map the neurological correlates of mental acts is dependent upon accurate understanding and articulation of these same mental acts. As Henman states: “The goal is greater understanding of these mental acts and their neurochemical antecedents, all the while recognizing that working out such correlations is not the same as identifying the acts with their correlates.” (2)

Scientists are conscious, mental actors

Next, as I have mentioned elsewhere, scientists design, execute, and reproduce the results of experiments by following a set of heuristically structured and integrated conscious mental acts. As such, their performance of the scientific method is wholly and sufficiently accounted for by reference to these conscious mental acts.

Notably, the scientist both acquires the ability to perform such experiments and has any errors in methodology corrected through recourse to the same repeated set of conscious mental acts, no matter how implicit either the initial direction or subsequent correction might be.

The researcher has a problem she desires to resolve. The researcher desires to know what the cerebral correlates for problem-solving are in the brain. The researcher’s first task is to design an experiment that he or she believes will achieve the intended outcome. So, in question form: What form of experiment is required? The researcher puzzles and reflects on various possibilities, reviews other experiments by other researchers, until eventually an insight occurs (an aha! experience). This or that particular experiment should provide the outcome that the researcher is seeking. But the researcher does not know at this stage. She may search more literature on similar studies or set up mock experiments in an attempt to verify her former insight. Certainty need not be the goal, but she may feel sufficiently convinced that the form of experiment she has settled on is reasonable. The only way to verify that this confidence is warranted is to run the experiment. (3)

The bolded language above identifies the conscious mental acts that are operative as the scientist sets up an experiment.

As subjects, we know what it is to attend to something, to question, to wonder, to puzzle, to reflect, to judge, etc., and we easily recognize the difference between each of these operations. Further, these same conscious mental acts are elicited from test subjects through injunctions in order to gather the imaging data of the underlying neurological correlates.

Therefore, understanding and use of conscious mental acts are not only constitutive of current experimental methods in neuroscience, they are also constitutive of the scientific method itself.

Henman’s argument is that a robust theory of cognition, such as that articulated by Bernard Lonergan in his work Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, provides neuroscientists with the distinction and descriptions of the conscious mental acts and operations that their research depends upon.

All human knowing is performed through conscious mental acts

Finally, some will deny that any reference to the conscious mental acts of scientists is required to give an account of science. They claim that science is simply a set of social institutions and norms that function as error filters on all claims about reality. As such, science is merely the communal means of epistemically justifying propositions about the objective nature of reality.

But this understanding of science only accounts for the justificatory procedures of the science as product. It wholly ignores science as process as described above. The we’ll-catch-any-bad-thinking-at-the-tail-end approach is either epistemically lazy or jaded. Whichever the case, it does not even attempt to account for the design, execution, and reproduction of scientific experiments described above. At best, it is half an account of science, but even the half is inaccurate due to its incompleteness.

The reason they cannot wholly jettison conscious mental acts from a full and responsible account of scientific knowing is that these mental acts are constitutive of all cases of genuine human knowing, of which science is merely one instantiation.

All instances of human knowing, whether mathematical, scientific, commonsensical, metaphysical, or ethical repeat the same heuristically integrated structure of unrevisible mental acts or operations, each of which is consciously transparent to the knower as subject.

It would be truly odd to offer a scientific account of thinking that did not and could not account for the very phenomena of mental operations which produced the scientific account itself. Or worse, to deny that a proper understanding of the mental operations were even relevant to the task at hand.

We would be forced to acknowledge that such an account does not account for all the relevant data. One could give a neurological account of aspects of cognitive thinking, but more is required beyond the mere neurology. As Anuj Rastogi states in response to Henman’s article discussed above:

Collaboration among molecular biologists, psychologists, biochemists, and physicists is imperative for cognitive neuroscience to progress. Therefore, all independent lines of inquiry, from microscopy to large scale neuroimaging, must in one way or another contribute to a theory of thinking. Of course, brain scanning cannot solely explicate such a theory. (4)

Notes:

- Robert Henman, Can brain scanning and imaging techniques contribute to a theory of thinking?, p. 49.

- ibid., 52.

- ibid., p. 51.

- Anuj Rastogi, Brain network commonality and the general empirical method, p. 68.

One thought on “Neuroscience cannot dispense with conscious mental acts”