Part I in this series of posts can be found here.

Methodological and epistemological claims

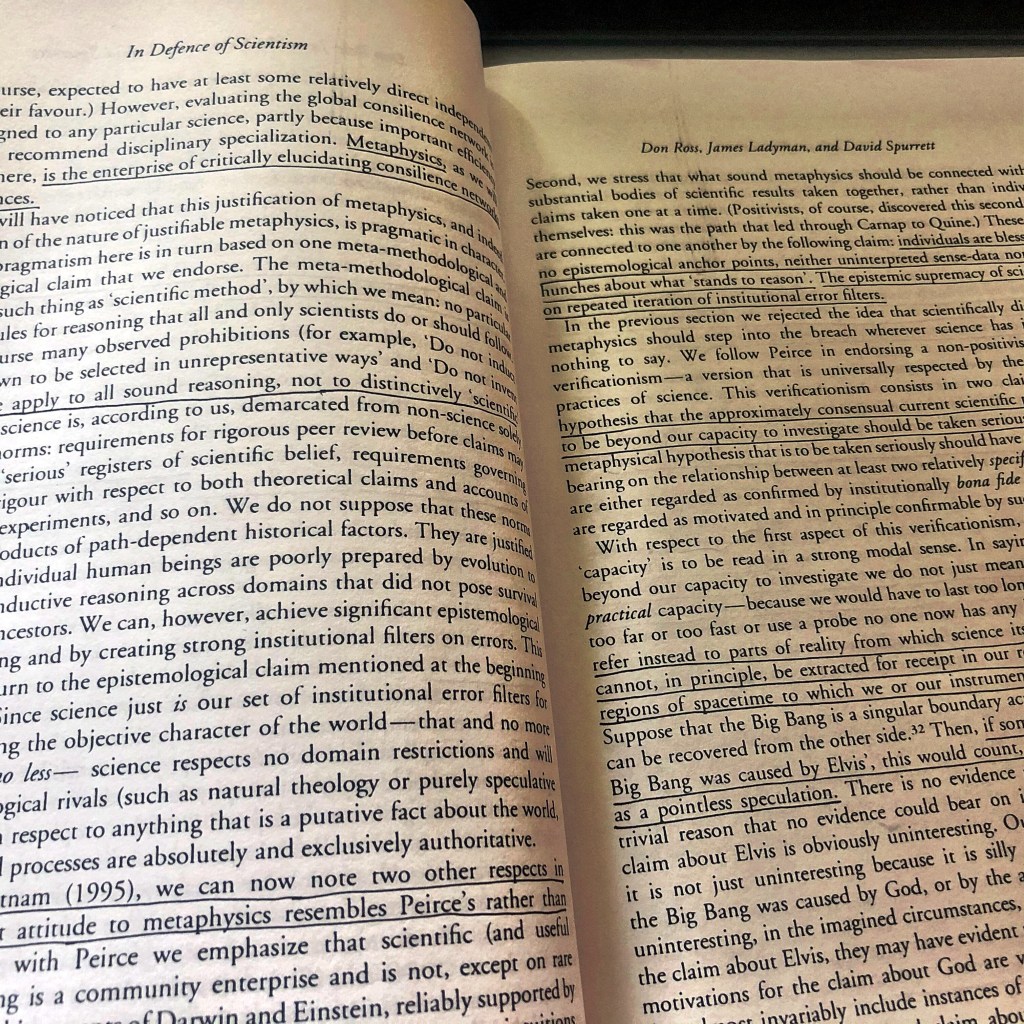

Ladyman and Ross make two claims, one meta-methodological and one epistemological, that serve to reinforce their naturalism as well as further the case against the domestication of science. First, the meta-methodological claim is their attempt to address the demarcation between science and non-science. The authors claim that there is no such thing as “the scientific method” if by this one means a set of positive guidelines that are following by all and only scientists when they investigate the objective nature of reality. Instead, they argue that science is demarcated from non-science by appeal to a set of institutional norms and practices which govern scientific inquiry. Only those hypotheses about the nature of reality which “survive the institutional filters of science” can reasonably be assented to. Such norms include peer-reviewed, scientific journals that employ rigorous requirements for representation of theoretical claims, observations, and experiments; the grant proposal processes; and the institutional practice acknowledging that claims from the special sciences are not allowed to contradict the claims of fundamental physics.

Ladyman and Ross’s advocacy of the institutional view of science is related to their emphasis on the evolutionary facts of human cognitive capacities mentioned above. As previously noted, the individual human mind is poorly prepared by evolution to reason about the objects proper to scientific investigation without the “error filters” that the institutions of science provide. For Ladyman and Ross, science just is the set of error filters which are built into scientific institutions and norms, and govern legitimate scientific practice. As such, their second, epistemological claim is that only the methods for investigating the objective nature of reality which are governed by these scientific institutions are epistemologically authoritative. Thus, science admits no epistemic rivals in its pursuit to explore the nature of the world since no other form of inquiry can guarantee its pursuit of truth and knowledge through the sort of self-correcting means that scientific institutions employ. It is not surprising, then, that Ladyman and Ross have entitled chapter 1 of their work “In Defense of Scientism.”

Two additional points follow from their institutional understanding of science. First, one the whole, science is understood as a communal enterprise rather than one that is engaged in by isolated, independent individuals. Scientific institutions, then, serve as a shared framework that brings together the research, results, and discoveries of physically and temporally disconnected, individual scientists; therefore, scientific institutions are the mechanism by which scientific endeavors become communal activities. Second, any metaphysical claims about the nature of objective reality should be motivated by scientific results taken as a whole rather than as isolated, individual statements. As scientific institutions aggregate the efforts of scientists across time and space so that they can work together, both confirming or disconfirming one another’s findings, so too should metaphysical claims be connected to groups of scientific claims rather than isolated, individual statements.

Metaphysics naturalized

The above meta-methodological and epistemological claims directly inform Ladyman and Ross’s naturalized metaphysics. Furthermore, these claims reveal that their naturalized metaphysics is more Peircean than Positivist. In fact, Ladyman and Ross claim that their metaphysics is a Peircean research programme built upon Peirce’s version of verificationism, which mirrors just the sort of practice in which scientific institutions engage. Since precisely what this verificationism amounts to is stated as their Principle of Naturalistic Closure, I cite that here:

Any new metaphysical claim that is to be taken seriously at time t should be motivated by, and only by, the service it would perform, if true, in showing how two or more specific scientific hypotheses, at least one of which is drawn from fundamental physics, jointly explain more than the sum of what is explained by the two hypotheses taken separately.

Stipulation: A ‘scientific hypothesis’ is understood as an hypothesis that is taken seriously by institutionally bona fide science at t.

Stipulation: A ‘specific scientific hypothesis’ is one that has been directly investigated and confirmed by institutionally bona fide scientific activity prior to t or is one that might be investigated at or after t, in the absence of constraints resulting from engineering, physiological, or economic restrictions or their combination, as the primary object of attempted verification, falsification, or quantitative refinement, where this activity is part of an objective research project fundable by a bona fide scientific research funding body.

Stipulation: An ‘objective research project’ has the primary purpose of establishing objective facts about nature that would, if accepted on the basis of the project, be expected to continue to be accepted by inquirers aiming to maximize their stock of true beliefs, notwithstanding shifts in the inquirers’ practical, commercial, or ideological preferences.1

The Principle of Naturalistic Closure (henceforth PNC) is intended to provide a heuristic limit to the sorts of metaphysical hypotheses that are considered open to investigation by metaphysicians. Since scientists look to the error filters instantiated in scientific institutions in order to assess the value of any particular hypothesis about the nature of the world and since science has no epistemic rivals, metaphysicians too should look to these error filters when assessing the value of their own hypotheses.

However, the PNC contains an additional claim about the nature of metaphysics, namely that “metaphysics…is motivated exclusively by attempts to unify hypotheses and theories that are taken seriously by contemporary science.”2 In other words, the task of metaphysicians is to unify the sciences.

There are two reasons for this. First, to repeat, science is the sole, legitimate means of investigating reality. Second, there is no specific discipline within science that attempts to unify the contents of the various sciences. As such, Ladyman and Ross think that this task falls most logically to naturalistic metaphysicians, the intended goal being “to articulate and assess global consilience relations across bodies of scientifically generated beliefs.”3

The principle which should guide metaphysicians in this task is what Ladyman and Ross call the Primacy of Physics Constraint (henceforth PPC). The PPC is stated as follows:

Special science hypotheses that conflict with fundamental physics, or such consensus as there is in fundamental physics, should be rejected for that reason alone. Fundamental physical hypotheses are not symmetrically hostage to the conclusions of the special sciences.4

The PPC states what is already common practice for the scientific community and is considered an institutional norm and error filter by Ladyman and Ross. Presupposed by the PPC, however, is the ability to clearly distinguish fundamental physics from the special sciences in some epistemically significant way, which Ladyman and Ross believe they possess. However, before getting to their account of that, I will develop their account of Ontic Structural Realism, its implications for metaphysics, and the relation of fundamental physics to the special sciences that it implies.

Notes

- James Ladyman and Don Ross, Every Thing Must Go, p. 30.

- ibid., p. 1.

- ibid., p. 30.

- ibid., p. 44.

One thought on “The argument of Every Thing Must Go (Part II)”